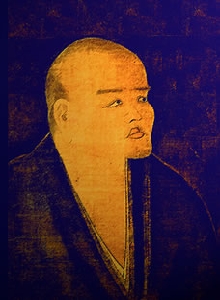

Dogen, taken from the cover art of Shobogenzo, by Nishijima and Cross, published by Doegn Sangha, and reproduced courtesy of Hokyo-ji Fukui prefecture..

[tweetmeme=”TheBuddhaWay]

Zazen is somewhat exacting in terms of form. It’s not easy to do full lotus with hands perched in the enlightenment mudra for 30, 45 minutes or an hour. And it’s also true that the physical posture alone with a certain focus on breathing does not equate to doing zazen. I’m going to make an argument in this post. That is that the intention of zazen, the Bodhisattva Vow, is formless, and as such makes zazen zazen. The form of it isn’t formless from the standpoint of reason, but the form of this special kind of intention is not really like other intentions. This intention alone among all intentions leads to the formless state of the Ultimate, because it originates from the formless, is informed by form, and yet is free of all form and all intention at the same time. This is because this intention of zazen, which is itself the Bodhisattva Vow, is itself an outgrowth of the Ultimate, which is conceptually born of the imaginary, informed by form in the guise of abstractions and words and gestures and texts and teachings used to formulate and construct it, and yet is free of all of those various forms, abstractions, and imaginings. In fact, the Ultimate alone has this unique property among all the feelings and other types of forms that go into experience. In fact, one could say that it is not truly experienceable in that regard, if we take form to be a crucial element of experience, because the Ultimate itself is not form or compounded in reality, but is an exalted and free state of mind wherein we relate towards the phenomena of sensory perception and mental formations, which together produce our experiences. In the language and spirit of the Sandhinirmocana Sutra and of Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika, the Ultimate is alone the uncompounded in a cosmos of otherwise compounded things. The Ultimate, as the state of awareness that is self-aware and yet free of attachment and aversion and ignorance, is most fit to dispense with form, feelings, perceptions, all other mental states and all mental objects, and all experience, because it alone is free of them, uncontrolled by them, though it arises in the midst of and through them. You could say it is actually an Ultimate Mind which goes to the heart of not just the mind itself, but to the heart of all existence as illusory, dependently co-arisen and ultimately empty of self-importance.

The objects of awareness of this Ultimate Mind may be determined by karma, true enough, but the state itself is actually not, for it is ultimately a way of relating to phenomena, including objects of the mind and all other mental states. This is the realm of the Buddhas and of the profoundly advanced bodhisattvas which strive to become being-saving Buddhas, many of which may be saints or even lowly mortal practitioners just like you and I.

It is for the sake of reaching this place where all things become possible, this place of the uncompounded Ultimate which is free of all the formal elements used to climb up to it, that we undertake the practice of zazen, or “dhyana”, or concentration practice for those familiar with the Six Paramitas. This zazen is the mode and method of the Tathagatas throughout all space and time. This is the basic and fundamental vehicle of self-examination used to see beyond the construct of “Self” into the Ultimate, which is nothing to do with Self, because the Self is thus transcended.

It would be a mistake to assume that this spirit of zazen, which is just the Bodhisattva’s Vow to reconnect with the Ultimate and further bring it out into everyday experience, is the beginning and end on the the topic, however. We live in a world of form, of space and time, and therefore we need formal guide rails in getting our bodies into proper alignment and positioning, breathing, focus, etc. Dogen provides much of these for us in one of the fascicles of what later became his body of work entitled the Shobogenzo. The title of this particular fascicle is “Fukanzazengi”, which follows below (because you really ought to read it).

Practical meditation guidance by the founder of Soto Zen in Japan, Eihei Dogen (1200-1253), entitled “Fukanzazengi”:

Fukanzazengi (“Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen”)

The way is originally perfect and all-pervading. How could it be contingent on practice and realization? The true vehicle is self-sufficient. What need is there for special effort? Indeed, the whole body is free from dust. Who could believe in a means to brush it clean? It is never apart from this very place; what is the use of traveling around to practice? And yet, if there is a hairsbreadth deviation, it is like the gap between heaven and earth. If the least like or dislike arises, the mind is lost in confusion. Suppose you are confident in your understanding and rich in enlightenment, gaining the wisdom that knows at a glance, attaining the way and clarifying the mind, arousing an aspiration to reach for the heavens. You are playing in the entranceway, but you are still short of the vital path of emancipation.

Consider the Buddha: although he was wise at birth, the traces of his six years of upright sitting can yet be seen. As for Bodhidharma, although he had received the mind-seal, his nine years of facing a wall is celebrated still. If even the ancient sages were like this, how can we today dispense with wholehearted practice?

Therefore, put aside the intellectual practice of investigating words and chasing phrases, and learn to take the backward step that turns the light and shines it inward. . Body and mind of themselves will drop away, and your original face will manifest. If you want to realize such, get to work on such right now.

For practicing Zen, a quiet room is suitable. Eat and drink moderately. Put aside all involvements and suspend all affairs. Do not think “good” or “bad.” Do not judge true or false. Give up the operations of mind, intellect, and consciousness; stop measuring with thoughts, ideas, and views. Have no designs on becoming a buddha. How could that be limited to sitting or lying down?

At your sitting place, spread out a thick mat and put a cushion on it. Sit either in the full-lotus or half-lotus position. In the full-lotus position, first place your right foot on your left thigh, then your left foot on your right thigh. In the half-lotus, simply place your left foot on your right thigh. Tie your robes loosely and arrange them neatly. Then place your right hand on your left leg and your left hand on your right palm, thumb-tips lightly touching. Straighten your body and sit upright, leaning neither left nor right, neither forward nor backward. Align your ears with your shoulders and your nose with your navel. Rest the tip of your tongue against the front of the roof of your mouth, with teeth together and lips shut. Always keep your eyes open and breathe softly through your nose.

Once you have adjusted your posture, take a breath and exhale fully, rock your body right and left, and settle into steady, immovable sitting. Think of not thinking, “Not thinking -what kind of thinking is that?” Nonthinking. This is the essential art of zazen.

The zazen I speak of is not meditation practice. It is simply the dharma gate of joyful ease, the practice realization of totally culminated enlightenment. It is the koan realized; traps and snares can never reach it. If you grasp the point, you are like a dragon gaining the water, like a tiger taking to the mountains. For you must know that the true dharma appears of it self, so that from the start dullness and distraction are struck aside.

When you arise from sitting, move slowly and quietly, calmly and deliberately. Do not rise suddenly or abruptly. In surveying the past, we find that transcendence of both mundane and sacred, and dying while either sitting or standing, have all depended entirely on the power of zazen.

In addition, triggering awakening with a finger, a banner, a needle, or a mallet, and effecting realization with a whisk, a fist, a staff, or a shout -these cannot be under-: stood by discriminative thinking; much less can they be known through the practice of supernatural power. They must represent conduct beyond seeing and hearing. Are they not a standard prior to knowledge and views?

This being the case, intelligence or lack of it is not an issue; make no distinction between the dull and the sharp-witted. If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, that in itself is wholeheartedly engaging the way. Practice-realization is naturally undefiled. Going forward -is, after all, an everyday affair.

In general, in our world and others, in both India and China, all equally hold the buddha-seal. While each lineage expresses its own style, they are all simply devoted to sitting, totally blocked in resolute stability. Although they say that there are ten thousand distinctions and a thousand variations, they just wholeheartedly engage the way in zazen. Why leave behind the seat in your own home to wander in vain through the dusty realms of other lands? If you make one misstep, you stumble past what is directly in front of you.

You have gained the pivotal opportunity of human form. Do not pass your days and nights in vain. You are taking care of the essential activity of the buddha-way. Who would take wasteful delight in the spark from a flintstone? Besides, form and substance are like the dew on the grass, the fortunes of life like a dart of lightning – emptied in an instant, vanished in a flash.

Please, honored followers of Zen, long accustomed to groping for the elephant, do not doubt the true dragon. Devote your energies to the way of direct pointing at the real. Revere the one who has gone beyond learning and is free from effort. Accord with the enlightenment of all the buddhas; succeed to the samadhi of all the ancestors. Continue to live in such a way, and you will be such a ‘ person’. The treasure store will open of it self, and you may enjoy it freely.

That’s Dogen on zazen. I look on him as the testy but wizened uncle of Zen who likes to defend Zen (really, Buddhism) against the classifiers and practitioners of “Zen”–and for good reason.

Buddhism isn’t just concerned for living human beings. It’s concerned about all beings, or you might say more pointedly, for all being. This includes animals, hell beings, human beings, alien beings somwhere (out there), and yes, even the dead (as in the peacefully resting in various heavens, as in those suffering in various hells, as in hungry ghosts roaming their old haunts). So, if you have questions, insights, or ordinary human comments to make, may I make a recommendation? That you just make your gesture for the sake of all beings in all times and directions who need to voice what you need to, but maybe unlike you, do not have the opportunity, or even the voice. Your sincere and wholehearted participation in your world (and this blog, which is part of your world) benefits all beings, always, whether you may know it or not.

The “dharma gate of joyful ease” is the transition that was mentioned that can happen when condition C from the previous post is present?

No, not exactly. Condition C from the previous post was about breaking through the constraints of egoic identification and into the ground of being which our bodies and minds are in reality rooted in (the ego is a reflection in a mirror of where we stand in the matrix of causes and conditions of co-arising). The dharma gate of joyful ease is letting go of ego-goals such as “Become a buddha ASAP!” or “I’ll need to do my taxes when I’m done meditating”. They are related, though, by both being ways of overcoming egoic identification–but they aren’t the same method exactly.

The “dharma gate of joyful ease” is basically another way of saying shikantaza, which is the Soto Zen tradition of “just sitting”. Dogen compares Soto and Rinzai at various points. This technique still emphasized in Soto today is an antidote to spiritual ambition, something which became a major stumbling block for many Zen practitioners (mainly monks), many of which went crazy trying to break through to enlightenment at breakneck speed.

The monks in later Chinese Ch’an became like any other career-faring person in the secular world, and this was recognized as a problem (stress and unease of spirit were the problem to begin with). The dharma gate of joyful ease is about taking your time and focusing on quality practice, resigning yourself to never getting the reward of supreme enlightenment (or even significant progress) in this lifetime, slowing down and practicing because it is enjoyable and enlightening in the moment, moment-by-moment, for an entire lifetime of such joyful practice and meditation (really, meditative living). Dogen says “zazen is enlightenment”. This is what the dharma gate of joyful ease means. The element of joy is something the initial jhanas are characterized by, in particular the first two jhanas.

The act of doing zazen is enlightenment itself, here and now, whether it lasts a fleeting moment or a lifetime. We all tap into the same enlightened state. It’s one state, despite all the “levels” (jhanas). When we first start doing meditation, we’re like a wine-taster with no palette as yet developed. We don’t know what we’re tasting yet, or how to evaluate wines. Advanced meditators can discern/intuit more and more of what they’re engaged with in the meditative state, and then dispense with the less necessary elements as they see through their more mundane aspects. For example, the discursive thought from jhana 1 wears of at level 2, and so on. There is probably nothing really new in terms of territory to be covered, only in terms of capacity to fully discern/see that territory as experiential territory. We move from a conditioned attachment to forms into varying degrees of unattachment to forms. The ultimate enlightenment is typically characterized by words like “formless” and phrases like “neither perception nor non-perception”. These are pretty meaningless to most people who meditate, but some advanced meditators can comprehend what it means to perceive yet not perceive in a formless mode.

Having said all of that…yes, the dharma gate of joyful ease could become present after condition C is reached, just not necessarily. Instead, you could have a very intense “burning through defilements” brought on by intensely elevated concentration. Joyful ease is one way to experience zazen/enlightening and it is a perfectly good way, especially when the will to burn through isn’t felt to be as present (let’s say you had less nourishing food that day, or are tired). Rinzai, however, is characterized by a perceived emphasis (it’s actually quite real…) on burning through defilements. So you might say that someone like the more recent Yasutani Roshi is somewhat antagonistic in spirit to Dogen’s “joyful ease” approach. Yasutani Roshi believes that the life or death seriousness of zazen ought to be turned up, rather than worry about taking it easy (everyone gets tired or has an off day/week). He believes this to be a valuable element from the Rinzai lineage. I would say that it’s always a life or death serious affair, but that we have to pace ourselves most of the time, and take full advantage of our excess steam to burn through defilements when it’s the right time (seshins are a good time for this in my view, though not according to everyone), so I think both sides are right at different times.

Pingback: Be still (for 12 hrs straight) my all day Zazenkai meditation | travelgem